Today's guest writer, Dave Tabler of the popular blog Appalachian History, presents the evidence. We'll let you be the judge.

Do you think this claim holds water? If so, is it time to change the North Carolina license plate? And what about our history books; if Micajah Clark Dyer flew decades earlier that the Wright brothers, how should we tell the first in flight story?

*

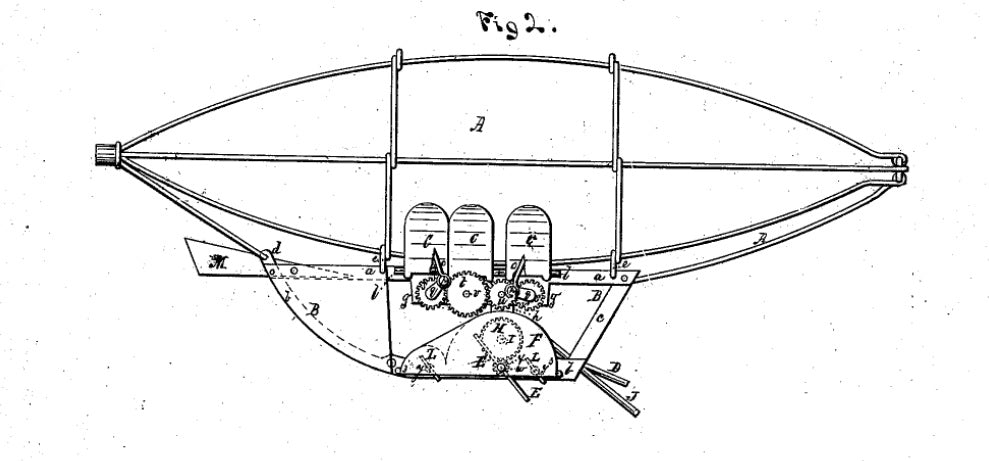

Micajah Clark Dyer (1822-1891) filed patent 154,654 for his ‘Apparatus for navigating the air’ in 1874, a full 29 years before the Wright brothers made their historic first flight.

Be it known that I, Micajah Dyer, of Blairsville, in the county of Union and State of Georgia, have invented certain new and useful Improvements in Apparatus for Navigating the Air; and I do declare the following to be a full, clear and exact description of the invention, such as will enable others skilled in the art to which it pertains to make and use it, reference being had to the accompanying drawings, which form part of this specification…

Witnesses at Choestoe, Georgia to Micajah Dyer’s illustrated and written patent document were Francis M. Swain (a neighbor) and M. C. Dyer, Jr. (the “other” Micajah Clark Dyer who, to distinguish the two, signed Jr. after his name. He was an uncle to the inventor Micajah Clark Dyer, but they were reared as brothers by Elisha Dyer, Jr., grandfather of Micajah). The document was dated February 16, 1874. It was filed in the patent office on June 10, 1874, and was approved there on September 1, 1874.

[caption id="attachment_9268" align="alignleft" width="271"]

Clark Dyer and his wife Morena, photo courtesy Union County Historical Society.[/caption]

Clark Dyer and his wife Morena, photo courtesy Union County Historical Society.[/caption]“When he was not busy with cultivating the land on his farm and tilling the crops necessary to the economy of his large family, Clark Dyer labored in his workshop,” says his descendant Ethlene Dyer Jones.

“There he experimented with a flying machine made of lightweight cured river canes and covered with cloth. Drawings on the flyleaves of the family Bible, now in the possession of one of Clark’s great, great grandsons, show how he thought out the engineering technicalities of motion and counter-motion by a series of rotational whirligigs. He built a ramp on the side of the mountain and succeeded in getting his flying machine airborne for a short time.

“Evidently, to hide his contraption from curious eyes, and to keep his invention a secret from those who would think him strange and wasting time from necessary farm work, Clark kept his machine out of sight, stored behind lock and key in his barn. Those who did not ridicule the inventor were allowed to see the fabulous machine. Among them were the following who bore testimony to seeing the plane; namely, his grandson, Johnny Wimpey, son of Morena and James A. Wimpey; a cousin Herschel A. Dyer, son of Bluford Elisha and Sarah Evaline Souther Dyer; and James Washington Lance, son of the Rev. John H. and Caroline Turner Lance.

“Just when the fabulous trial flights (more than one) occurred on the mountainside in Choestoe is uncertain [about 1872-1874.] Prior to his death, he had invented a perpetual motion machine. It is also a part of family legend that Clark’s son, Mancil Pruitt Dyer, turned down an offer of $30,000 for the purchase of his father’s pending patents on inventions, especially the perpetual motion machine. Maybe Mancil reasoned that if he held out for more, he could receive it. Still another family story holds that Clark’s widow, Morena Ownbey Dyer, sold the flying machine and its design to the Redwine Brothers, manufacturers of Atlanta, who, in turn, sold the ideas to the Wright Brothers of North Carolina in about 1900.”

“Mr. Dyer has been studying the subject of air navigation for thirty years,” says the Macon (Georgia) Telegraph and Messenger, June 27, 1875, “and has tried various experiments during that time, all of which failed until he adopted his present plan. He obtained his idea from the eagle, and taking that king of birds for his model has constructed his machine so as to imitate his pattern as nearly as possible. Whatever may be the fate of Mr. Dyer’s patent, he, himself, has the most unshaken faith in its success, and is ready, as soon as a machine can be constructed, to board the ship and commit himself, not to the waves, but to the wind.”

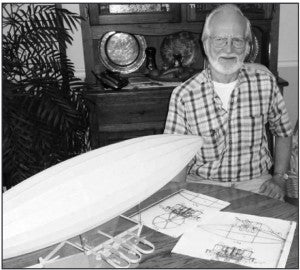

[caption id="attachment_9261" align="alignright" width="270"]

Dyer descendant Jack Allen, a retired Delta Airlines mechanic. crafted every piece of Clark Dyer’s airplane model to scale. Photo courtesy of The Towns County Herald.[/caption]

Dyer descendant Jack Allen, a retired Delta Airlines mechanic. crafted every piece of Clark Dyer’s airplane model to scale. Photo courtesy of The Towns County Herald.[/caption]“We had a call on Thursday from Mr. Micajah Dyer, of Union county, who has recently obtained a patent for an apparatus for navigating the air,” adds a July 31, 1875 article in the Gainesville (Georgia) Eagle. “The machine is certainly a most ingenious one, containing principles entirely new to aeronauts, and which the patentee confidently believes have solved the knotty problem of air navigation. The body of the machine in shape resembles that of the fowl, an eagle, for instance, and is intended to be propelled by different kinds of devices, to wit: Wings and paddle-wheels, both to be simultaneously operated, through the instrumentality of mechanism connected with the driving power.

“In operating the machinery the wings receive an upward and downward motion, in the manner of the wings of a bird, the outer ends yielding as they are raised, but opening out and then remaining rigid while being depressed. The wings, if desired, may be set at an angle so as to propel forward as well as to raise the machine in the air. The paddle-wheels are intended to be used for propelling the machine, in the same way that a vessel is propelled in water. An instrument answering to a rudder is attached for guiding the machine. A balloon is to be used for elevating the flying ship, after which it is to be guided and controlled at the pleasure of its occupants.”

Clark Dyer later invented a spring-loaded, propeller-driven flying machine, according to several witnesses who saw him launch a successful model. Legend says he later personally flew in a full-size one with foot controls and a steering device. He would glide from a mountainside in Choestoe, on a rail-like ramp of his own design.

“Mr. Dyer has worked thirty years on his machine,” said his neighbor John M. Rich in a letter to the editor of the Athens Banner-Watchman from April 28, 1885. “He is not crazed, but is in dead earnest, and confidently believes that he has solved the problem of aerial navigation. He is not a crank nor a fanatic, but is a good, quiet citizen and a successful farmer.”

“People said he continued to work on perfecting the machine until his death on January 26, 1891 at age 68,” says Clark Dyer’s great, great granddaughter, Sylvia Dyer Turnage. “Since the patent we’ve found was registered on September 1, 1874, I believe he had a later and more advanced design in those 17 years.”